Automagically Managing Releases for GIFwrapped

Posted 8 years, 1 week ago.

On a recent episode of Independence, we talked a little bit about our approaches to managing tasks, especially related to version releases. Something I didn’t get into is that, over the past few months, I’ve been attempting to improve my workflow with a number of automations; both to reduce the busy work I have to get done, and to make it so that things update without me as much as possible.

This is something of a living project all its own—each time I get through a release cycle I re-evaluate and tweak a little—but as a result it’s almost like having a project manager… albeit a very tiny one.

Oh Trello, My Trello

After a long period of trying to get Wunderlist to handle the intricacies of my task list, I ended up moving to Trello. This meant I could see across my roadmap much more easily, and improved my workflow significantly.

Green for new features, yellow for improvements, and red for bugs. Purple indicates that I haven’t been able to replicate it yet, and black means it only affects the beta.

At any given time, my board has around five lists: one for Feature Requests, another for Known Issues, and the rest are specific to a version release on the horizon. Because I follow regular ol’ semantic versioning (haters gonna hate), that’s one for the next major, minor and patch release. Right now, there’s a column for v2.0, v1.7, and v1.6.6.

My general workflow goes something like this: any time a user requests a feature, or lets me know of a bug, I add a card to one of the first two lists. When they graduate to being part of a planned release, they move over to the appropriate version. Once I’ve finished working on that, I write a description that becomes part of the release notes.

When a card’s feature (or fix) goes out to Testflight for beta testing, the card gets archived, and then once the version is shipped to the App Store, the list for that version is also archived (and any leftover cards moved to the next appropriate version).

This approach is nothing amazing, and it even has a few flaws (such as the fact that it doesn’t track any of the stuff not related to specific releases, like marketing)… but overall I find it works. The real value, of course, is in how it extends outside of Trello.

Bug Fixes and Performance Improvements

GIFwrapped has always had interesting release notes. That said, they’ve taken on a more traditional appearance (being a list of changes within the given version) as the app has aged, partly because I’ve gotten lazier, but also because it’s more informative than a recipe for hot chocolate or a badly-written screenplay.

Lists are also much easier to automate, which is why a lot of developers’ first instinct is to use their version control commits as the source of their release notes, but this doesn’t work for me: I find the result to be less than ideal.

My approach is to write a couple of sentences into the card’s description on Trello once I’ve completed the work (allowing me to write the note while the task is still fresh), and then a list is automatically generated with all the notes each time a build goes to Testflight. All this is handled with a script in fastlane (and a little creative use of the Trello API).

Because each card represents a feature or bug, this reduces the number of potential entries down to just those affecting users. It’s also had a huge effect on the time I used to spend looking back over my work and putting them together by hand, from a couple hours down to maybe 30 minutes. All the while, I still get to write something fun—and occasionally nonsensical—while maintaining a separation between marketing and code.

This was my first foray into automating a part of my release cycle, and when I noticed that it cut down the amount of pain I had to go through for each release, I was hooked.

Automating All the Things

The next logical step was to automate the stuff that happens when a release is shipped to Testflight, as well as when it goes to the App Store. I set up scripts that handle the archiving of the relevant cards and versions for me, plus the creation of lists for new versions, so when v1.6.5 shipped recently, its list was archived, and v1.6.6 was automatically set up with cards I hadn’t completed yet. I hooked these up to iTunes Connect by triggering them based on the relevant notification emails that get sent (though, I’d kill for proper webhooks).

From there, it made sense for it do other things too. Each time a new beta is released, a full set of notes are generated and attached to a pull request on GitHub, minus any cards that were specific to beta builds (because sometimes I break things). On release to the App Store, the final, edited text is copied to automatically update the user guide with the release notes. These also get copied to the new press kit repository.

Speaking of the press kit, pushing new content to that repository causes the relevant page on the GIFwrapped site to rebuild as necessary, automatically displaying new images and relevant text.

Merging a pull request (which, if it’s not obvious yet, is how I manage my version releases while they’re in progress) to master causes a tag/release to be automatically created on GitHub, and allows me to roll code back to an exact release if I ever need to.

Avoiding the Killer Robots

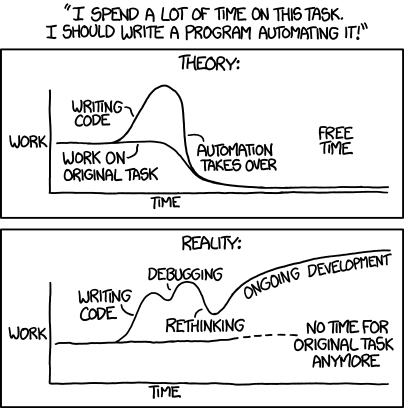

The obvious risk of building any sort of automation is that it can gradually take over your entire focus (like how robots will take over our jobs eventually). I mean… it’s so common, that there’s a well-known XKCD comic that illustrates this beautifully.

This is totally fine if you have something you want to make a career out of (which is kinda what being a software engineer is all about anyway, when you think about it), but when it comes to automating tasks to truly give yourself more time, there’s a few things to keep in mind so you can avoid just having to manage them instead.

1. Size Matters

The best automations are the ones where they take an input, and do one repeatable thing with it, just like a function. My automation for creating tags from a merged pull request has very simple parameters, and it would be terribly difficult for it to fail in unexpected ways.

- GitHub calls webhook on pull request being closed or merged.

- If the origin and destination branches aren’t correct, ignore.

- Get the relevant commit for the merged pull request.

- Get the relevant details for the pull request, like the name and message.

- Create a tag with the commit, including data from the pull request.

I use a specific pattern in naming the branches for my versions, i.e. version/1.6.6. This clearly denotes it as a specific kind of branch, includes the intended marketing version, and also conveniently groups it in Tower.

2. Fail Loudly, Offer Solutions

I’ve taken to using a Slack webhook to post a message when any particular automation fails. This avoids situations where I’m left wondering what happened, and allows me to jump on it quickly if it’s important (like updating the user-guide), even from my iPhone.

Slack posts can also include buttons, which can make responding to a failed task much quicker and easier. A direct link to the pull request, and one to reattempt the automation script is a great first step to resolving any issues. It certainly beats having to find the pull request, and then manually create the tag with all the relevant information, that’s for sure.

3. One Step Begets Another

The greatest benefit to having a number of small automations is that you can string them together to create much more complex workflows. Even better is that it allows you to kick them off at any point along the way, if you need to.

In addition to my tag-creating script for example, I have a seperate one that collects the information about all existing tags (and pull requests) into a JSON file, which gets used as a source point for the user-guide contents, amongst other things.

- GitHub calls webhook on tag being created or pushed.

- Get the relevant details for the tag, like the name and message.

- If the tag’s name is not a valid marketing version, ignore.

- Add or update details in JSON file.

The benefit to this is that this doesn’t get run if the pull request automation fails, and it will run if I create the tag manually for some reason. Each step is simple in and of itself, but create a complex system when combined. Like a less exciting Voltron.

4. Stop, Evaluate, and Listen

Each time I go through a release cycle, I take a second to consider how it went. Not only does this give me a bit of a break from the code, but it gets me asking questions about how I get work done.

- What went according to plan? What broke?

- Are my automations working as intended?

- Did I spend time on things that could be automated?

- Do I want to try a different approach to anything?

At this point, more often than not, things are going according to plan, and I can (mostly) release without a lot of manual work. Editing the release notes, submitting the release, and posting a tweet are really the only things I do manually (unless anything fails or breaks).

There’s always room to change, though. Do I want to have the tweet posted for me? Could I write it in advance, and have it posted when the build rolls out? I don’t necessarily have to answer this question now, but it’s something to think about, and it can inform changes in how I manage my releases going forward.